I am in the process of becoming qualified to become a Forest School Leader, with the aim to run sessions in the future for all age groups. I have created a ‘policies and procedures handbook’ which includes risk assessments for every activity, accident plan, vision statement, qualifications, forest school principals, safe working procedures, risk benefit plan, and insurance details. So far, I have taught a range of lessons over a couple of weekends to a lovely family where they are learning new skills, cooking on the fire, and learning how to protect our woodland environment. Most importantly, they’ve had valuable time as a family where they can bond over their woodland experiences and chat whilst toasting marshmallows over the fire.

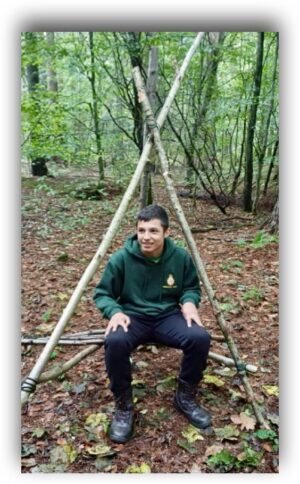

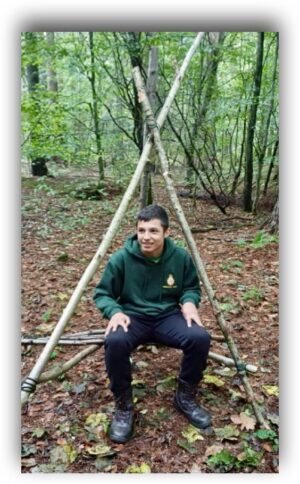

The first session was an introduction to what Forest School is all about and snippets of what I aim to deliver over the next few months. I met them at the station car park and walked them up to the woodland site and gave them a site orientation, identifying the boundaries and the admin area. They had a chance to explore the woods for themselves and then I gave a knot tying lesson.  I demonstrated a few different types of knots including the reef knot and clove hitch, and they were able to practice these by making a rope swing, putting up ponchos and making a tripod chair. The real challenge was to see if they could sit on it with their whole-body weight!

I demonstrated a few different types of knots including the reef knot and clove hitch, and they were able to practice these by making a rope swing, putting up ponchos and making a tripod chair. The real challenge was to see if they could sit on it with their whole-body weight!

Fire starting was the next activity and they got stuck in straight away and collected deadwood from the ground and formed the sticks up. After a few attempts at striking their flints and lots of perseverance, they got the fire going and layered on the sticks to keep it a light. This was not complete without toasted marshmallows on sticks, s’mores and a hot chocolate! Listening to the crackling of the fire, the warmth on their faces, the gooey marshmallows and good conversations were their favourite part of the day. They also had a lesson on a different type of fire, a Dakota firepit. Here, they learnt the benefits of having an underground fire and what they can cook too on it. Like every lesson, we talk about leaving no trace, so it was important that the end of the session we cleared away all the burnt sticks and logs and picked up any litter.

The second session we learnt about the layout of a woodland and all the animals. Working from the ground layer all the way to the canopy, we identified different animals and species that live or roam here. We discussed the benefits of natural habitats, human disturbance, and how we can encourage animals into the area. By learning to appreciate our surroundings, our respect and love for the outdoors will last forever.

After giving them a few ideas, they individually went away and made their own habitats. They came up with really creative ideas and it was fantastic to see them thinking about how they can protect the animals and keep them safe. They came up with a bird hide, tripod shelter, bug hotel, and tee-pee tent. It was great to see them using their knot tying skills from the previous session and putting it into practice. At the end of the lesson, we all walked around everyone’s habitats so they could describe and show off what they have made.

Today’s session was all about cooking on the fire. They went straight into collecting sticks to burn on the fire, logs for the boundaries, and sticks for whittling so they can put their food onto them for toasting. The first challenge was preparing the food mixture to make damper bread; they got all the ingredients into a bowl and made a very sticky job of mixing it with their hands! Once they had a nice doughy mixture, they spun it around their sticks and started toasting them on the fire. Having a nice burnt, crispy outer dough with a drizzle of hot honey was by far the favourite!

Next, we learnt how to cook on the embers, and of course, there are only two ways to teach this, popcorn and chocolate banana boats! This went down a treat as they hadn’t had this before; they prepared their chocolates in bananas, wrapped it up in tin foil, and using a fire glove, they put them onto the embers for 5 minutes. 5 minutes of cooking, 30 seconds of eating and they were all gone, success! The popcorn was also a hit, listening to the popping against the tins and then drizzling hot honey sauce over them to make them nice and sweet. With all this tasty work, we couldn’t go a miss without having a hot chocolate. We put stakes into the ground either side of the fire pit, laid a log across the top and hung our kettle from the middle over the flames.

What was really nice to observe was the fact that they were all communicating when making the damper bread, chatting away whilst collecting sticks, and having a laugh whilst waiting for their food to cook was priceless. Meaningful conversations in an outdoor environment are so valuable and good for everyone’s wellbeing and this is at the forefront of why I want to become a forest school leader.

Laura

]]>

Recent research with the orchid Cremasta variabilis has revealed some interesting facts about the germination of the seeds. The orchid is found on the Korean Peninsula and is an insect pollinated, terrestrial orchid. As with other orchids, its seeds are minute and are known to depend on a certain fungus to grow and develop. In the past, most studies have focused on the fungi present in mature orchids but the team from Kobe University studied very young seedlings. They noted that seedlings were often to be found near decaying logs, and this led them to test whether deadwood fungi are involved in early orchid development.

Recent research with the orchid Cremasta variabilis has revealed some interesting facts about the germination of the seeds. The orchid is found on the Korean Peninsula and is an insect pollinated, terrestrial orchid. As with other orchids, its seeds are minute and are known to depend on a certain fungus to grow and develop. In the past, most studies have focused on the fungi present in mature orchids but the team from Kobe University studied very young seedlings. They noted that seedlings were often to be found near decaying logs, and this led them to test whether deadwood fungi are involved in early orchid development.

Now,

Now,

At night, moths were the only insect visitors of the pale pink / white flowers of the bramble, and they also proved to be very effective pollinators. It is not clear why moths were more effective, perhaps the time they spend visiting a flower is a critical factor.

At night, moths were the only insect visitors of the pale pink / white flowers of the bramble, and they also proved to be very effective pollinators. It is not clear why moths were more effective, perhaps the time they spend visiting a flower is a critical factor. But moths face an additional challenge - artificial light at night. This interferes with the

But moths face an additional challenge - artificial light at night. This interferes with the

The list contains both native and non-native species, the aim is to create through planting stronger and more biodiverse woodlands that can tolerate our changing climate over the coming decades. The rate of climate change is the main issue. Whilst some of the trees already grow here, others come come from warmer / drier areas, such as the Mediterranean or

The list contains both native and non-native species, the aim is to create through planting stronger and more biodiverse woodlands that can tolerate our changing climate over the coming decades. The rate of climate change is the main issue. Whilst some of the trees already grow here, others come come from warmer / drier areas, such as the Mediterranean or

Ladybirds in gardens help control aphids on roses and other plants by feeding on them.

Ladybirds in gardens help control aphids on roses and other plants by feeding on them.

A number of government agencies have produced booklets / downloadable files (PDFs) on how to address the possible problems associated with the changing climate.

A number of government agencies have produced booklets / downloadable files (PDFs) on how to address the possible problems associated with the changing climate.

.

. In the last week we have managed to strim a path right around the perimeter to our fence line. The site has become our “happy place “ which our adult children also love. We have big plans for its future, creating paths, educating future generations and becoming good caretakers for the future of this beautiful place.

In the last week we have managed to strim a path right around the perimeter to our fence line. The site has become our “happy place “ which our adult children also love. We have big plans for its future, creating paths, educating future generations and becoming good caretakers for the future of this beautiful place.

I demonstrated a few different types of knots including the reef knot and clove hitch, and they were able to practice these by making a rope swing, putting up ponchos and making a tripod chair. The real challenge was to see if they could sit on it with their whole-body weight!

I demonstrated a few different types of knots including the reef knot and clove hitch, and they were able to practice these by making a rope swing, putting up ponchos and making a tripod chair. The real challenge was to see if they could sit on it with their whole-body weight!